5 of My Takeaways from Hunt, Gather, Parent

I read Hunt, Gather, Parent almost a year and a half ago, and the fact that I’m still motivated to chat about it after all these months should tell you something! While it did take me some time to move this post to the top of the queue, it’s not for lack of enthusiasm. This is one of the most interesting, unique, and actionable parenting books I’ve read in awhile, and one I still think about often in our daily interactions as a family. And it’s one I regularly reference in conversation, so this post feels like a natural extension!

A brief summary for the unfamiliar: the author, Michaeleen Doucleff (with her three-year-old daughter!), visits three of the oldest cultures in the world: the Maya in the Yucatan Peninsula, Inuit families in the Arctic Circle, and Hadzabe families in Tanzania. All have found success raising happy, helpful, well-adjusted children, and her mission is to understand why by living with families – and applying their techniques to her own daughter along the way. She shares her findings (including lots of practical takeaways) with the goal of resetting the American paradigm, restoring sanity to parenting, and creating better outcomes for our kids.

The Maya culture, with their unusually helpful, generous, and loyal kids, is the one that inspired Michaeleen to write the book. It’s the section I got the most out of, too – when I went back to look over my notes to write this post, I had far more starred and underlined ideas than I had room to share!

Here are five that have particularly stuck with me:

1. Quit entertaining and instead invite. This starts from the beginning and continues until the teen years. “Toss out the idea that you have to ‘entertain’ the baby with toys and other ‘enrichment’ devices. Your daily chores are more than enough entertainment,” Michaeleen writes from her time with the Maya. I loved this insistence on inviting the child in to the work of the family from the youngest ages (and reminding us that toddlers find it terribly exciting to be invited in). She also describes how Maya parents never discourage a toddler who wants to help, even when they seem rude (like pulling a broom out of the parent’s hand).

“On the flip side, if you constantly discourage a child from helping, they believe they have a different role in the family,” Michaeleen writes. “Their role is to play or move out of the way. Another way to put it: If you tell a child enough times, ‘No, you’re not involved in this chore,’ eventually the child will believe you and will stop wanting to help. Children will come to learn helping is not their responsibility.”

Something else that stood out to me: the Maya continue to do chores alongside the child long after Westerners often want children to do a chore alone. For Westerners, the goal is often to get kids to the point of independence with a chore, but for the Maya, “the invitation is always for together, for doing the chore together.” Of course, the kids will eventually become independently competent. But personally, this freed me from a lot of the frustration of feeling like the goal should be to hand off a task. That’s no longer my immediate goal.

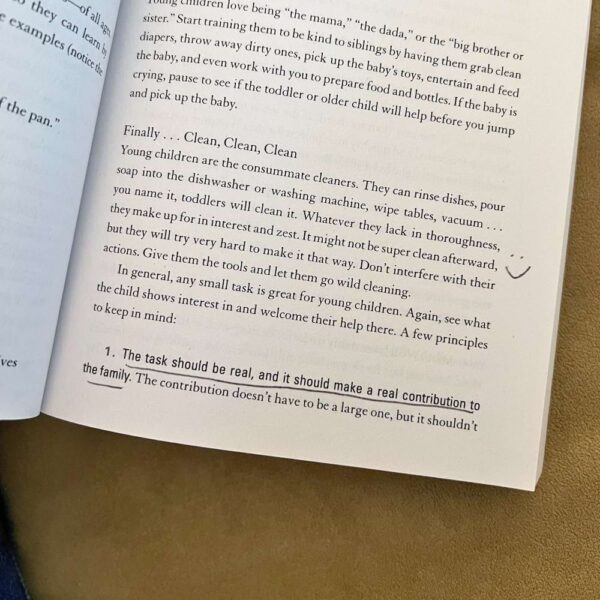

2. Make small asks. Michaeleen describes how the Maya fold in “small, quick, easy tasks that help another person—or the whole family. These are requests performed alongside the parents for a common goal. They are often subtasks of a larger one (e.g., holding the door open while you take the garbage out). “And they are often tiny,” Michaeleen notes, “I mean tiny, tiny (e.g., putting away one pot in the cabinet that’s across the kitchen, grabbing a bowl from the cabinet), but they are real. They really help.”

I loved this takeaway and implemented it immediately. It’s small ((Michaeleen recommends 3 or 4 requests a day) and perhaps obvious, but I hope it will make a big impact long-term. I think it’s a continual reminder to my children that their time is not only their own, that we are all a part of the work of the household and that they are needed and wanted.

3. Try activation. “Instead of explicitly telling the child to do a task, activate their help by telling them you’re starting a chore or by giving a hint that a chore is needed,” Michaeleen describes. By pointing out things like, “it looks like the dog’s water bowl is empty,” or “time to take the trash out,” or “the laundry just dinged,” we’re teaching kids to notice without nagging. Of course, they won’t always respond as we hope, but they’re learning, little by little.

4. Ditch the child-centered activities. Maya parents structure their family’s time to spend the majority of it together, living daily life alongside one another. They do very few, if any, child-centered activities, and Michaeleen also comes away recommending ditching almost all toys. This will feel radical (and even mean!) to some parents.

But in their place, she writes, the Maya parents give their children an even richer experience, something that many Western kids do not get much of: real life. “Maya parents welcome children into the adult world and give them full access to the adults’ lives, including their work,” she notes. Kids are nearby when adults work around the house, take care of the family business, or maintain the family garden. “And young children actually love these activities,” she notes. “They crave them. If we get kids involved in adult activities, that’s play for kids. And then they associate chores with a fun, positive activity.” A virtuous cycle!

While we haven’t thrown away all of our toys or ditched all child-centered activities, I think about this often. This perspective has given us extra freedom to say no to things like kids’ birthday parties that split our time and drive us apart, and instead spend our leisure time doing things we all enjoy together, like going for a bike ride, hiking, swimming at the pool, or playing a board game.

5. Answer misbehavior with more responsibility. We have found this to be incredibly effective with our children. Is one of them whining? Complaining? Harassing a sibling? Throwing toys? We invite them to come work alongside us or direct them to a job that needs doing. While my initial instinct is to get frustrated, speak sharply, or try to make a quick patch of the situation, inviting them in instead of sending them away is often much more effective. Again, at its best, it shows them we need them and we want them in the family, giving them the value and attention they’re seeking in a healthy way. It recalls them to their best self.

There is SO MUCH MORE I could say on this first section alone (let alone the other sections – parenting with calmness! Practicing silence! Child-child teaching! Telling family stories!) but I want to leave you with just enough to whet your appetite for more :)

I’ll end with this. At the beginning of the book, Michaeleen goes to great pains to make the point that the communities she visits are “just like us,” and I get it—on the surface, they might seem different (remote locations, unfamiliar traditions), and she wants to forestall her readers brushing off their advice as irrelevant. In the end, though, I loved that they are different, and unencumbered by many of the beliefs, expectations, and traditions that American culture is saddled with. This book was a neat opportunity to relearn the value in some ancient wisdom that, indeed, American culture generally does find irrelevant or backward. I’ve found it helpful and thought-provoking, and if you decide to read this book, I hope you do, too!

Now, I’d love to hear: If you’ve read Hunt, Gather, Parent, did you have a favorite takeaway? If not, have I motivated you to pick up a copy? : ) Any thoughts about these takeaways?

Affiliate links are used in this post!

I haven’t read this but just added it to my hold list at the library. A few of these concepts are already employed at our house (inviting, asking for small bits of help), and a few are new to me (activation) and reinforce things we’re trying to model and teach (problem solving).

I’m generally reminded of some advice from my mom about transparency– kids like knowing what the adults are doing, and they like being part of it. When it’s a chore, no little bit of it is too small to carve of to be done with enthusiasm, not perfection. When it’s leisure, it’s part of why I read paper books rather than on my phone or an e-reader. It’s clear what I’m doing, and it’s easy to do the same. And the feel of a book in one’s hands!

YES, Leigh! Our very first Articles Club article was an essay about transparency and teaching with kids and how phones obscure so much. Has stuck with me ever since!

I remember loving this book last year! I think you had recommended it to me. Reading this post made me realize I had forgotten a lot of it, so I am encouraged to check it back out at the library and give it a second read-through. This book, along with “All Joy, No Fun” and “No Such Thing as Bad Weather” are my personal favorite parenting books I’ve read so far!

Love all of these takeaways, but especially the one about not needing to entertain our children. A whole book could be written about that one alone!

I had forgotten so much, too! SO SO many gems in here!

I read this earlier this year (also at your recommendation) — I actually read most of it while I was nursing Foster! It has proven to be super important for my mental state with him because he’s never been that interested in toys and always wants to be with me. Thinking about the things that Michaeleen writes about makes me much more likely to accept this with patience rather than wishing he’d just go play by himself! I haven’t read a ton of parenting books, but this one is my favorite so far!

I just finished this book and it was so fun to see this post, because I keep wanting to talk to people about this book! I think my favorite take away was inviting young children into our daily chores and also outings ( I think she mentions the grocery store and maybe even a book store?). My daughter is only 8 months old so she can’t really help yet, but even popping her in the baby carrier while I cook or accomplish tasks around the house makes me feel like I can include her in a small way :)

My husband and I read this earlier this year and we talk about it all the time! I love the techniques you highlighted. One I try to remember is giving a look instead of saying no or reprimanding. We often ask our 2 year old, are you being a good listener? after giving directions, and he almost always decides to obey after being called out.

One of my favorite books this year! From your thoughts, I could not agree more with doing activities that drive us together rather than splitting us up. As our kids get older and there are more potential events on our calendar, it feels like the cultural norm for one parent to take one kid and another parent to take another kid. We recently made the decision on Saturday mornings to do things together as a family as much as possible which does mean saying no to other possible activities, but we think it will be worth it to have those sweet memories of all 5 of us together.

For me, one of the biggest applications was just learning to talk less when giving instructions. She talks about witnessing simple one or two word directions or even just modeling what is happening next to help the child learn to know what to do. It helped me realize how often I get caught up with too many words and she has helped me be so much more mindful of how I give instructions.